¡Prepárese para el gran final! Nuestra introducción histórica a Espartaco: Roma amenazada concluye con un dramático enfrentamiento que le dejará en vilo.

Don’t miss out on this thrilling conclusion! Read the previous chapters here and prepare to be captivated by the story of Spartacus.

– Parte 1

– Parte 2

– Parte 3

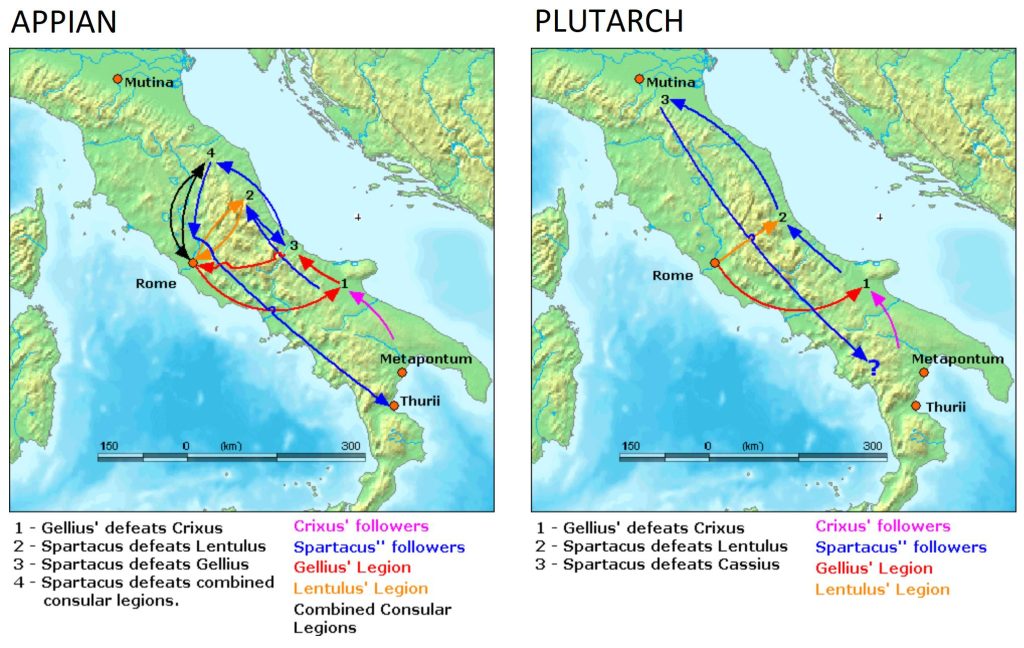

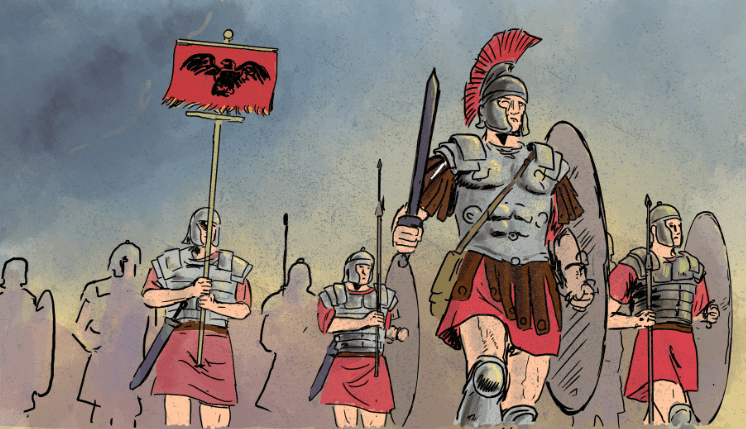

After suppressing Quintus Sertorius’s rebellion in Hispania, Pompey’s legions were returning to Italy. While sources differ on whether Crassus had specifically requested reinforcements, the Senate seized the opportunity of Pompey’s return to Italy and ordered him to bypass Rome and head south to assist Crassus in suppressing the slave revolt. To further bolster Crassus’s forces, the Senate also dispatched reinforcements under the command of Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, the proconsul of Macedonia.

Apprehended by the prospect of losing credit for the war to the arriving reinforcements, Crassus intensified his efforts to swiftly quell the slave revolt. Spartacus, anticipating Pompey’s approach, attempted to negotiate an end to the conflict with Crassus but was met with refusal.

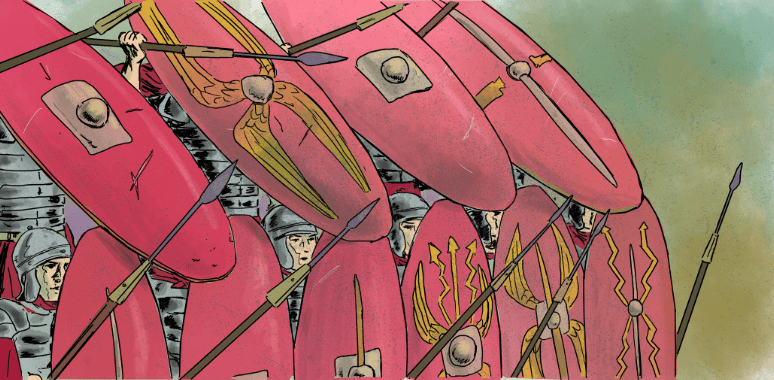

As a result, Spartacus and his army broke through the Roman fortifications and retreated towards the Bruttium peninsula, followed closely by Crassus’s legions. In a skirmish with a portion of Spartacus’s army led by Gannicus and Castus, Crassus’s forces inflicted a significant defeat, killing 12,300 rebels.

Despite heavy losses, Crassus’ legions were struggling to contain Spartacus’s rebel army. The Roman cavalry, led by Lucius Quinctius, was ambushed and annihilated by escaping slaves. As the rebels’ morale faltered, they began to splinter, launching desperate attacks against Crassus’ forces.

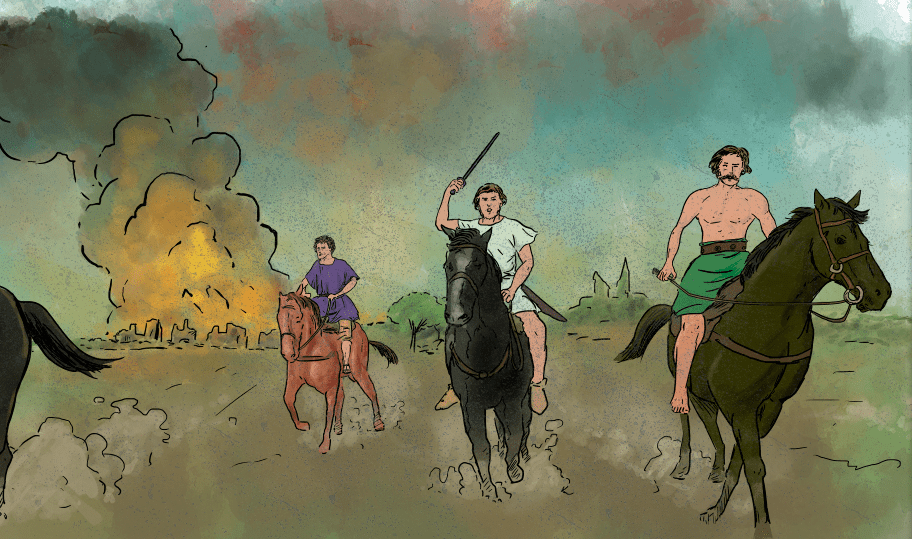

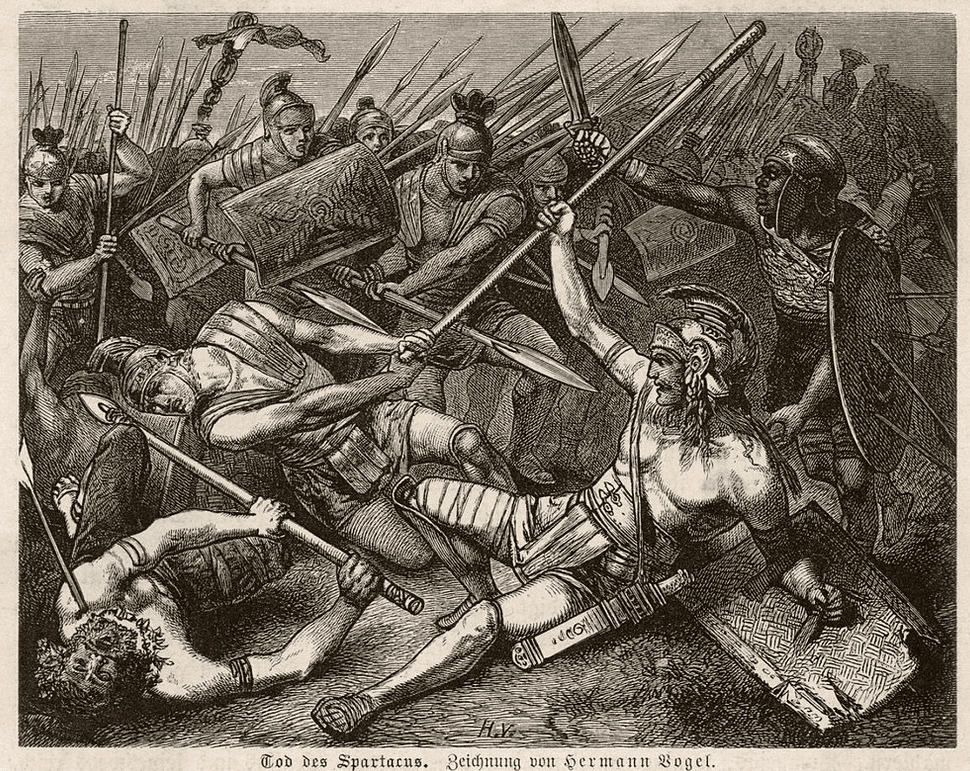

En una última y desesperada batalla en el río Silarius, Espartaco, el legendario gladiador convertido en líder rebelde, hizo un gesto dramático que simbolizaba su inquebrantable determinación. Mató a su caballo delante de sus tropas, declarando que la victoria traería más caballos, pero que la muerte los haría innecesarios. Este acto, tal vez imbuido de un significado ritual, marcó el tono del baño de sangre subsiguiente.

Espartaco avanzó con intenciones feroces, abriendo una brecha en las filas enemigas. Se creía que su objetivo final era Craso, el general romano que lideraba las fuerzas enemigas. Sin embargo, a pesar de sus valientes esfuerzos, Espartaco cayó bajo una lluvia de flechas y su cuerpo quedó irreconocible en medio de la carnicería. La victoria romana fue decisiva, y Craso, para infundir miedo a los posibles rebeldes, ordenó la crucifixión de 6.000 prisioneros supervivientes a lo largo de la Vía Apia. Aunque los historiadores antiguos afirmaron que Espartaco pereció en la batalla, su cuerpo nunca fue recuperado. La Tercera Guerra Servil llegó a su fin con la victoria decisiva de Craso.

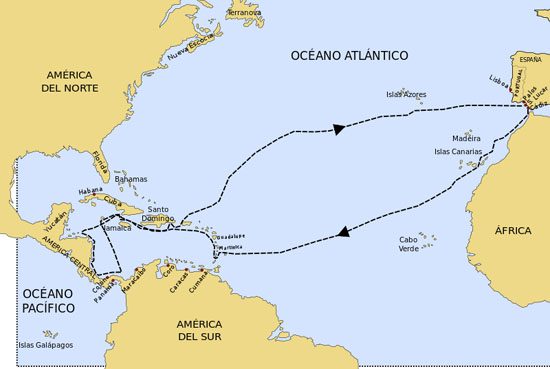

The war, however, was not yet over. Numerous fugitives attempted to escape northward, only to be intercepted by Pompey’s army in Etruria. Pompey’s annihilation of these remnants of the rebellion secured his own claim to fame and overshadowed Crassus’s earlier victory. He boasted that while Crassus had defeated the slaves in battle, he had eradicated the war’s very roots.

Despite his defeat and death, Spartacus’s legacy endured. His name became synonymous with rebellion and resistance, a symbol of hope for the oppressed. While Crassus and Pompey, the victorious generals, eventually met tragic ends, Spartacus’s memory lived on as a mythical hero of freedom.

La Tercera Guerra Servil fue el último gran levantamiento de esclavos de la historia romana. Roma no experimentaría otra rebelión de esta magnitud en los siglos venideros.